David L. Meth

ARTY’S POOLROOM

A Three-Act Dramatic Comedy

• Feature Length Screenplay •

• Multi-season TV Series •

• ARTY’S POOLROOM fills in the gap left among such long-form TV series, such as The Deuce, The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel, Mad Men, Boardwalk Empire, Magic City, and Vinyl. In other words, it has not yet been done. Not only would this be a success on or off Broadway, but it can be written as a sensational multi-season series production for HBO, Netflix, Amazon Prime, Showtime, or AMC. • My research, personal library, and sources are meticulous and exhaustive. •

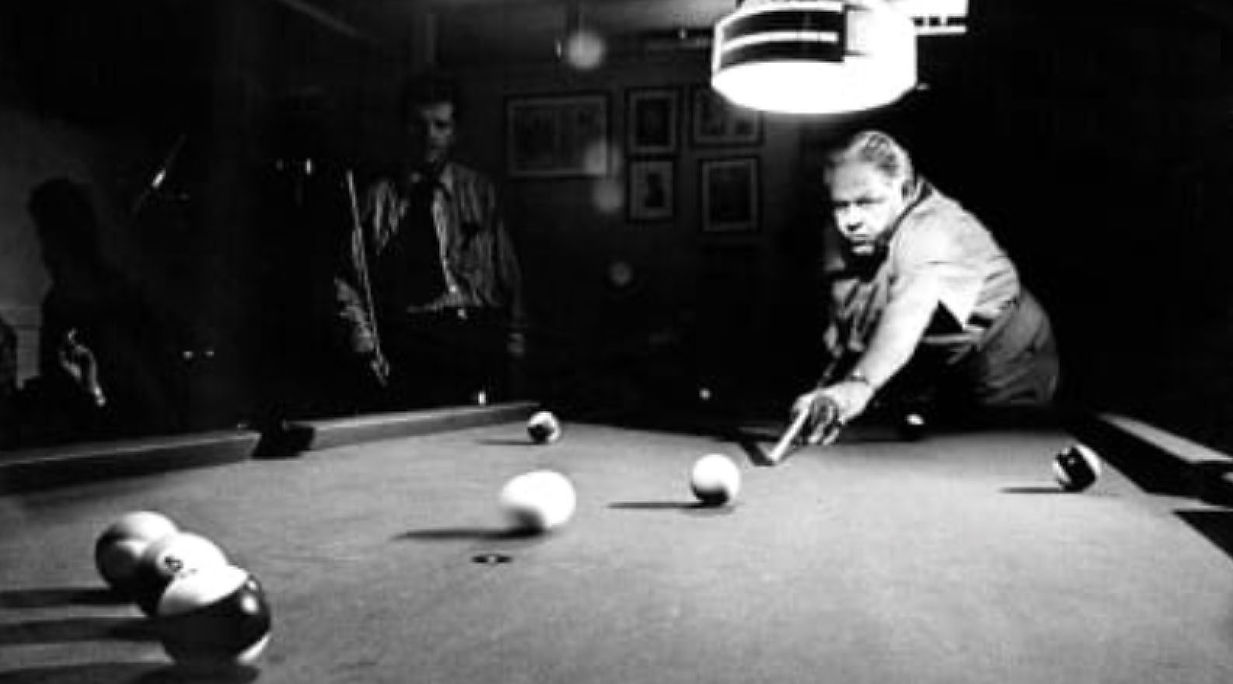

The play opens in Arty’s Poolroom, a dark, cavernous stone basement swathed in shadows and bathing in smoke that is lifted in the fluorescent lights of low-hanging lamps over old claw and ball-footed pool tables with leather pockets. In steps Irving Polanski, a “broken down valise”, a high school student indebted to some rather nasty locals for gambling. But Irving carries a heavier burden and introduces one of several overlapping themes in the play: the meaning of life and death/survival and existence—he is the only son of a Holocaust survivor and the last of the bloodline. Should he fail in any way, it is a failure for the generations that died under Hitler, and a failure for generations that he is responsible for bringing into the world.

This is in contrast to the view of the father of “Loose” Larry Leonard, one of Irving’s wise-cracking friends. Ben Leonard died on the operating table while having a blood clot in his leg removed; but he was revived after three or four seconds, and now considers life from a new perspective: he has been given a second chance and is driven to succeed—in business, as he struggles to establish himself on his own; and in family, as he oversees the raising of his three children—while his marriage falls apart in front of the eyes of his eldest son Larry.

Vulnerability is also a theme of the play: Irving is vulnerable with every step he takes. Afraid to go home to face his parents, he rides all night in his friend’s gypsy cab, reducing his father to embarrassing searches in Arty’s, or to sorrowful pleas from the street level stairs. He is bullied by Brute, a massive psychopath who sees himself as a primitive warlord. He is beholden to Jerry, Brute’s older brother and a gambler who preys upon the regulars down at Arty’s, including Irving’s best friend Zimmerman—a 16 year old who can’t get his shoelaces tied right, or his coat buttons lined up. Neither can he keep his mouth closed, no matter how many teeth it costs him; yet, he has the peculiar quality of a visionary who has not yet found his medium.

ARTY’S POOLROOM is alternately a war zone and an escape, but always a place of release, relief and bonding, where the future is being dreamed, and events of change are slowly being acknowledged. Arty is the referee, the soft elderly man and owner of the poolroom who would just like to retire instead of baby-sitting other people’s high school children and delinquents. But he cannot change his course now: he must put up with abuse and snide remarks, or quit and collect unemployment. He is not so old or so soft, however, that he does not fight back. Nor does he lack a sense of humor or wisdom: He admonishes everyone to get out and to stay out—or their lives will turn out to be like his without an education. Only Irving sees him as a success.

ARTY’S POOLROOM is written in fast, lean dialogue—in the quick-talking street language of 60s Brooklyn, where a remark doesn’t go unchallenged and a challenge doesn’t go unanswered. The dialogue is carried on in Arty’s Poolroom by the kids, and in the Old Dutch Diner by the adults. The conversations overlap, like a thought coming to mind during a discussion, but they never seem to take place directly between father and son who read each other’s mind without being able to speak directly to each other about the issues confronting them: the break up of family as it used to be known—Larry’s parents get divorced; the gradual socialization of drugs—Irving overdoses; the Vietnam war—Zimmerman’s brother returns crippled; and the general inequality of life—Brute, the warrior, never gets drafted.